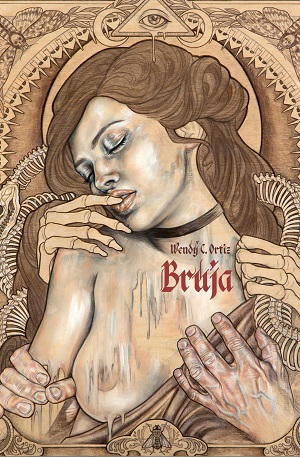

Bruja, by Wendy Ortiz

Bruja, by Wendy Ortiz

There is quite the argument going on about the significance of dreams. Psychological and neurological studies of dreams often lean toward the conclusion that dreams are nothing more than the random firing of neurons displaying a kaleidoscopic patina of memories, fantasies, and nightmares. I am sure that many of you, and I include myself in that number, have felt a deep and poignant significance to dreams, especially as they relate to the creative process. In Wendy Ortiz’s dreamoir, Bruja, she finds an utterly fascinating middle ground between the two perspectives. Except that even “middle ground” is insufficient; rather, she presents an inclusive, paradigm-shifting theory in narrative form, one that embraces the interconnectedness of stories, focalization, the unconscious, and how we construct reality.

By the nature of our physical senses, our perceptions of reality are inherently reconstructions. Every conscious (and many an unconscious) moment, our minds take in information from the immediate past and assemble a structure that helps us to make workable sense out of existence. In a very real sense, reality is a story we tell ourselves. Bruja utilizes this concept to its fullest extent, but with an important constraint – it chooses to abandon any pretense of agreed upon linear structure. By tapping into the dreams of the narrator, the text accepts the at least partially arbitrary nature of time, cause and effect, and significance. While nominally organized by monthly chronological order, each section of the story delivers dream after dream, exhibiting the impossible alongside the cyclical and the seemingly random.

A silver shimmer moved through the outdoor fountain. A huge swordfish pushed through the water and hit air. Panic set in—the swordfish was the size of a small truck. I wanted to look but also wanted to run. I knew that many things would suddenly be growing huge in size. I wasn’t sure where to go.

This tone of delivery is thoroughly consistent throughout the book and it is beautifully appropriate. The absurd and the amazing are presented as matter-of-fact and curious. This flavor is not blasé and it is not meant to be; this comes from a perspective that routinely witnesses the miraculous and the terrible and which understands that they are not mutually exclusive, as if acknowledging the awe-inspiring while being ready to “run”.

One of the recurring elements in Bruja is packing and repacking luggage. It is usually delivered in an almost throwaway fashion, at the opening of a section, and it frames the text that follows. It is among the most significant symbolic acts in a text that one could argue is made entirely of symbolic acts. The ideas of always being on the move, of refusing to settle, of living moments of lives rather than merely a life, are all tremendously powerful. These ideas run smack into those of dreams as the narrator is quite literally packing and repacking these memories and fantasies and nightmares, rearranging them to see how they fit inside the container that is her own mind. There is, at times, an almost desperate, obsessive-compulsive drive to accomplish this.

I packed my bags at least three times. I was booked on a trip to New York but I wondered if I would ever make it because the damn bags needed to be packed and unpacked and packed again.

What the text is describing, among other things, is the process of trying to make sense of a life and its myriad possibilities. The narrator’s lovers meld together into a psychosexual amalgam, then fray apart into their own fragments in time. The narrator is at times passive and submissive and at other times violent, ecstatic, and enraged. Moreover, the experiences regularly refuse simple binary opposition – the text never renders judgment on behavior or beauty, because it cannot and remain honest. The first thing I did after finishing the book was read it a second time, backwards, and not an ounce of meaning was lost for me. Bruja remains loyal to one of its central themes: denying the linear mandatory primacy.

We had no sense of time; there was just the walking back and forth in this mysterious and beautiful place, knowing the beach was within walking distance.

I know I have been waxing philosophical in this review, but that is because I find Bruja so fascinating. Even its title feels wonderfully apt; bruja is the Spanish word for witch, and Ortiz has commandeered it to encapsulate the experience of a woman who, by coming to understand secret knowledge about the universe, manifests the power to manipulate reality itself. But, critically, the text never treats reality as an illusion. The traumas, the loves, the living that is shown and hinted at throughout the book are no less real for their continual metamorphoses. The malleable nature of experience does not render experience invalid or ineffectual. Bruja conveys all of this with a simple, graceful elegance, baring the vulnerabilities of a soul without fear of rejection or the pride of showmanship, but with a hope that the presence of the reader will manifest even more possibilities. It never forces you to reject your conclusions, but after reading it, you will be unable to accept your perspective as the only one.

Bruja is available now through Civil Coping Mechanisms.

Lost Privilege Company, or the book of listening

Lost Privilege Company, or the book of listening The Orchid Stories, by Kenward Elmslie

The Orchid Stories, by Kenward Elmslie Defiant Pose, by Stewart Home

Defiant Pose, by Stewart Home

Ford Over, by John Pluecker

Ford Over, by John Pluecker Here Lies Memory, by Doug Rice

Here Lies Memory, by Doug Rice