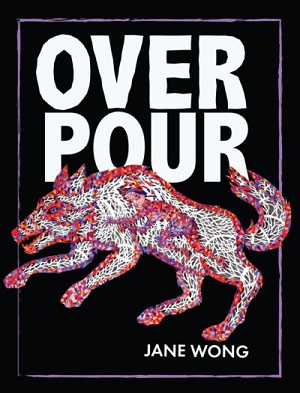

Overpour, by Jane Wong

Overpour, by Jane Wong

Jane Wong opens Overpour with, “For years I lived this way: with words / That had to do with carrion / I have learned to cast away my enemies / I have lit their insides clean.” Upon first read, the words captured me in a way I did not understand. I wrote them down on the post-it note I use as a bookmark and took the words with me as I read the rest of the collection. Each time I encountered lines that made me pause my reading, I read the post-it and tried to imagine its connection to the poem on the page. I was delightfully surprised that although Wong’s poetry is a reflection of different topics like nature, war, and animals, there is an interesting interweave of language occurring on the page (sometimes evident and sometimes you need a post-it to remind you).

Wong’s poetry reflects topics that are disorienting and, at times, slightly unfamiliar. However, the narrative style of poems allows the reader to follow and reflect on one’s role as a reader and participator. Many of Wong’s poems do something interesting: they pair up the city with the country, they pair up human and animal. However, these images are not spoken about in binaries where the reader gets one or the other. Instead, they are spoken about together and create an interesting conversation —a call and response, if you will. Within this ongoing conversation, Wong points to different questions that we should all be asking about our world; questions about violence, poverty, and fulfillment. Though there is no one answer, the themes of these poems force us to see ourselves in this struggle; a struggle that compels us to question our contribution to the problem and what it is we’re doing to solve it.

Overpour is divided into three different sections but perhaps what is most notable is how historical, political, and social contexts appear to haunt Wong’s poetry. In The Poetics of Haunting in Asian American Poetry (poeticsofhaunting.com), she states “A poetics of haunting insists on invocation: a deliberate, powerful, and provocative move towards haunted places. How does history —particularly the history of war, colonialism, and marginalization— impact the work of Asian American poets across time and space? How does language act as a haunting space of intervention and activism?” Wong’s poetry reflects her attempt to answer these questions. In doing so, she inhabits her mother’s voice in a series of poems titled Twenty-Four, Thirty, Twenty-Nine, Forty-Three, and Twenty-Five. Throughout these poems, the speaker exemplifies a search for the self. In Twenty-Four, the speaker writes about her marriage and having children. It is in this poem that the title makes an appearance: “Overpour, / of regret, there is too / much blood in a cow / to comprehend.” Here the speaker does anything but overpour the situation. In fact, this is only a snippet of this individual in this particular moment in time. There are still many years left to recount and as such, we are encouraged to read on. The rest of the poems in Wong’s collection are amalgamations of particular moments and memories. All of these moments deserve to be read —all at once or one at the time, you decide.

Overpour is available now through Action Books.