When I Spoke In Tongues, by Jessica Wilbanks

Review by Lily Blackburn

That some believe in a spiritual language, one that negates form but can be coaxed from silence – connecting one to a higher power – is the source of both seduction and doubt for Jessica Wilbanks in her memoir When I Spoke in Tongues.

Wilbanks down-to-earth eloquence draws us into the intimacy of her family and community before slowly revealing the growth of her doubt and the emotionally arduous process of untangling a self from a religious past.After leaving her faith behind – sanctifying the moment with her name and the date on a scrap of paper in a bathroom at age 15 –Wilbanks struggles to find satisfaction or a sense of purpose sans organized spirituality; she studies the origins of her faith in order to contextualize her own experience.

#

While magic may seem like an out of place word – it can only be said that church embodied both a magical and intimidating space for Wilbanks as a kid. Her descriptions of the congregation and scenes of worship are vivid, mystical.

“My mother’s lilting soprano joined my father’s baritone..My heart lifted in my chest and for the first time all day I felt like I could breathe…There was so much we wanted in that moment. We wanted to tap into the force that spun mountains and oceans out of air and take it into us.” These moments are undercut by a constant fear – of doing something wrong, falling inappropriately in her skirt if she, like her brother Obere, becomes too overcome with emotion. She yearns to feel what others feel around her, what she can’t yet articulate – the power of belief.

I watched Obere fall under the weight of the pastor’s hand. One moment my brother was standing there beside me and the next moment he’d darted backward in his boy boots, hitting the ground with all the force of a man…I wanted to fall too, more than anything. But when my turn came…my legs refused to give out.

As a teenager, Wilbanks’ father “finds” the journal harboring her feelings for her friend of the same sex and Wilbanks relationship to her family – her final connection to her faith – is altered immeasurably. Wilbanks captures this sudden and irreversible shift rendering a familiar kind of shame. “As night stretched over the lawn my parents studied me as if I was an intractable algebra problem. They couldn’t solve for X.” As someone who grew up in a secular household – it is difficult to completely wrap ones head around the kind of shame that people experience when the laws of a religious belief system separate someone from their own family; though simply having been a teenager can conjure this deep sense of isolation – that suddenly, having been honest with yourself, you are no longer the same person in the eyes of those you love most.

In college in Houston, Wilbanks begins to research the history of Pentecostal faith left out of the sermons of her childhood. While Pentecostal faith is a marginalized sect of Christianity in the states, it was once the fastest growing faith south of the equator. Wilbanks writes of what is known as the Azusa Street Revival – a gathering of thousands of people inspired by William Seymour, a black preacher under whose teachings brought together so many that one church’s foundations literally collapsed beneath the weight of an increasingly diverse crowd of white and black – young and old – drawing racist critics to deem the whole movement false, unworthy, unholy.

Wilbanks finds herself in Nigeria studying the intersections of Yoruba tradition and Pentecostalism, longing to be included once again in the rituals of her faith. “I thought maybe that old Holy Ghost language might still be wedged inside me somewhere after all, like a sleeping baby, waiting for the moment when I was no longer ashamed to let it out of my mouth.”

A sleeping baby not only embodying the innocence she feels she cannot claim, but the cosmetic purity that fills her with doubt; good versus evil – dichotomous thinking in the form of commercialized conversion narratives.

Near Lagos she attends the infamous Holy Ghost Services offered monthly at Redemption Camp – which typically draws between eighty and one hundred thousand people. It’s an oasis in comparison to daily life in Lagos.

As soon as we entered the gates I could see why people talked about the church headquarters as the promised land. After a few weeks in Nigeria, I’d become accustomed to power outages and traffic snarls. But Redemption Camp had constant power, running water, manicured landscapes, even flush toilets. Once inside, one was shocked by the order and calm.

Wilbanks is forced to reckon with not only her own privilege but the seeming lack of class consciousness in a camp for worship and spiritual connection – one that promises the message of “do good,” and you shall receive. It is inexplicably linked to and born from the passion and belief of the Azusa Street Revival. But even this interwoven arch of history, struggle and community against all odds is not enough to reconcile or her doubt.

The overall story becomes just as much a study on organized faith as it does relating the struggle of living post-faith. At the same time, the memoir’s trajectory offers a refreshing perspective on what forms self-discovery can take.

#

Wilbanks relates the human need for acceptance and community through a unique lens – revealing how language and story can shape or empower the ways we find them. In her city apartment, trying to forget the rural life she left behind, Wilbanks yearns to speak in tongues as she did as a child, struck by the syllables in a church bathroom – but she is long out of practice; moving her burrito to the side of her desk and entering a silent, zen state – she waits “clenching my fists in an effort to call up an entirely different self;” a young student mid-burrito just trying to feel something more in a moment of mundanity. The question for Wilbanks is, then, what is left? What does her life mean? It is Wilbanks ability to relate the experience of these larger questions that make When I Spoke in Tongues a relevant memoir in our divided present.

When I Spoke in Tongues is available now through Beacon Press.

Lily Blackburn is a writer and senior prose editor at Typehouse, a writer-run literary magazine. She lives in Portland, Oregon with her cat, Binx.

Inquisition, by Kazim Ali

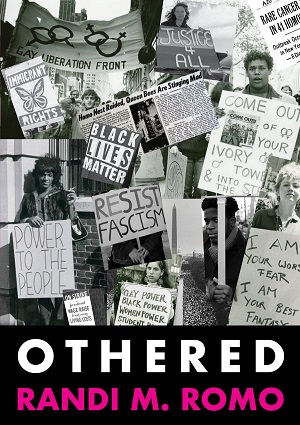

Inquisition, by Kazim Ali Othered, by Randi Romo

Othered, by Randi Romo Orange Lady, by Erika Ayón

Orange Lady, by Erika Ayón Cadavers, by Néstor Perlongher

Cadavers, by Néstor Perlongher There Are More Beautiful Things Than Beyonce,

There Are More Beautiful Things Than Beyonce, Hover the Bones, By Melisa Malvin-Middleton

Hover the Bones, By Melisa Malvin-Middleton

Collection by Roger Santiváñez

Collection by Roger Santiváñez Poetry collection by Marosa di Giorgio

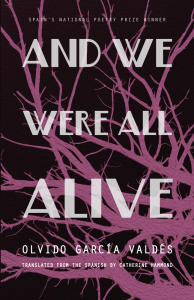

Poetry collection by Marosa di Giorgio Collection by Olvido García Valdés

Collection by Olvido García Valdés Review by Liz von Klemperer

Review by Liz von Klemperer