Fish in Exile, Vi Khi Nao

Fish in Exile, Vi Khi Nao

Many people have their own techniques for dealing with trauma. Some of these techniques are learned in the mouth of the dragon, born out of necessity and scars. Some are useless and catchy platitudes cooked up by people who have been blessedly free of real hardship. Many people on both sides, and along the rest of the spectrum, will offer their advice on how to emerge from the cages made of grief and loss. But ultimately the keys to those cages are all unique to the imprisoned individuals. Our ability to cope is crafted by our own hands and cannot be made for us. This is one of the ideas lying at the core of Vi Khi Nao’s beautiful and excruciating Fish in Exile, an unabashed immersion into one of the core agonies of the human experience and the rebounding echoes of its consequences. It is a novel of shatterings, where the best laid plans and boundaries are sundered and left to shape new perspectives.

The story at the core of Fish in Exile is not entirely unfamiliar – a couple that the novel names Ethos and Catholic are parents who have lost their two children to inexplicable happenstance on a beach. The novel centers around the relationship between Catholic and Ethos, two people who care deeply for one another but who are unable to cross the ocean of grief between them. But the way in which Vi Khi Nao breathes painful new life into the story is by taking it deeper that most any author would be comfortable venturing. No part of this experience is left sugar-coated or unexplored. The sexual tension between husband and wife bleeds through the text as they both yearn for intimacy from the person they love most but cannot psychologically dissociate intercourse from procreation in light of what has happened. This unreleased tension bubbles over toward taboo moments that threaten to shatter relationships and lives, ranging from the relatively mundane in the form of adultery to the illegal in the form of statutory and incest. Through the perspectives of side characters, we see how the parents become the objects of well-intentioned but completely ineffective gestures and gawking from their communities. The way in which societies often turn tragedies into spectacles is eviscerated by the novel as cruel and the height of selfishness. Even the reader is pulled into this critique, as we find ourselves engrossed in this sensory overload of sexual awkwardness and emotional loss.

She lifts the waistband of my briefs and lowers it to my thighs. The daisies crawl out, falling onto the comforter like confetti.

My wife stares at my eyes, and then at my deflowered penis. She alternates this ping-pong gaze for five seconds before wiping the daisies swiftly away from my penis and leaping off the bed. She sobs her way into the bathroom and closes the door.

The reason Vi Khi Nao is able to get the reader to sit and engage with this guilty excitement is because of some fantastic and exquisitely sharp prose. Fish in Exile reads quickly thanks to its effortless flow and direct delivery, and these lend themselves to riding the emotional wave that the book takes us through. The language is smart but not pedantic and it is wonderfully crafted in that special way that lets you forget you are reading text on the page as the words fit together. Nao then combines this with a clever structure for the novel that completes the effect of the experience. The book starts from Ethos’ perspective and we spend the first third of the text over his shoulder and in his mind, watching him struggle and fail to breach the defenses that Catholic has built around her body and mind. The middle section of the book is reserved for several of the important secondary characters, such as Callisto, Lidia, and Ethos’ mother, who attempt to fill the yawning gaps between the main characters and, at times, attempt to hold them together or drive them apart. The final section and say belongs to Catholic, who must deal with more pain and obstacles than any other character and whose arc ultimately shapes the narrative itself. This layout perfectly encapsulates the journey of the characters and the plot. I don’t know about you, but I find few things more satisfying than reading a book like this, where everything resonates and harmonizes throughout the text to reveal the meticulous care with which the novel was written.

How can I apologize if I don’t feel anything? If it doesn’t hurt to make an apology, why don’t I just do it? I decide I will make a point to apologize to him. But when? He has disappeared to another place in the house. The silence.

While on a personal note, I will also mention that, as a student of Greek mythology, I found Nao’s use of the Persephone myth and the callbacks to Greek tragedy to be beautifully handled. It is unfortunately common to see mythologies of the ancient world called upon in unsubtle and obtuse fashion, more for their “cool factor” than for any real metaphorical resonance. But here the novel handles the relationship with brutal sincerity and surprising levity simultaneously. In one go, the text highlights the patriarchy’s utter inability to fully understand or appreciate motherhood, the biological imperatives that form the foundation of parenthood, and the acceptance of the notion that grief can never really be extinguished, only embraced as part of the human experience. It shows that some things are even beyond the reach of gods, and yet no tragedy is so great that it cannot be overcome.

Given the intensity of the subject matter, I cannot recommend this novel for the purposes of an easy read. But I do encourage anyone who might have difficulty with such a notion to steel themselves and open Fish in Exile. It is a fantastic example of the beauty that can be found in tragedy and trauma, and I am not referring to the notion of happy endings. Rather, the resiliency and the capacity to work through difficulty are what are on display here.

Fish in Exile is available now through Coffee House Press.

The Warren, by Brian Evenson

The Warren, by Brian Evenson Bottom’s Dream, by Arno Schmidt

Bottom’s Dream, by Arno Schmidt Flowers Among the Carrion: Essays on the Gothic in Contemporary Poetry, by James Pate

Flowers Among the Carrion: Essays on the Gothic in Contemporary Poetry, by James Pate You Ask Me To Talk About the Interior, by Carolina Ebeid

You Ask Me To Talk About the Interior, by Carolina Ebeid Suite for Barbara Loden, by Nathalie Lèger

Suite for Barbara Loden, by Nathalie Lèger Bruja, by Wendy Ortiz

Bruja, by Wendy Ortiz Lost Privilege Company, or the book of listening

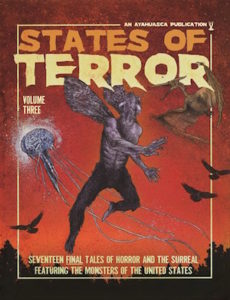

Lost Privilege Company, or the book of listening States of Terror, Vol. 3

States of Terror, Vol. 3 The Orchid Stories, by Kenward Elmslie

The Orchid Stories, by Kenward Elmslie Defiant Pose, by Stewart Home

Defiant Pose, by Stewart Home