My Damage: The Story of a Punk Rock Survivor

My Damage: The Story of a Punk Rock Survivor

by Keith Morris (with Jim Ruland)

Keith Morris, founding member of the classic Los Angeles hardcore punk bands Black Flag and Circle Jerks, has just released a new memoir that takes us back to the embryonic days of the Los Angeles punk scene. A career renaissance man, My Damage: The Story of a Punk Rock Survivor, charts Morris from his youth in the sleepy south bay town of Hermosa Beach, to his notorious stature as frontman of Black Flag and Circle Jerks, to his battle with diabetes and formation of OFF! My Damage strips away the legend of Morris and sheds light into areas of his life that have been unilluminated until now. With so many rock memoirs being bloated exercises in ego and hyperbole, My Damage takes the road less traveled and paints Morris as humble punk rock guru. The book ultimately solidifies Morris amongst the most likeable guys in a musical landscape that is filled with so many titanic egos.

My Damage: The Story of a Punk Rock Survivor was penned by Morris, with Jim Ruland (founder of local So-Cal reading series, “Vermin on the Mount”) lending a contributing hand. The book is written in a fairly conversational tone, with Morris’s deadpan, self-deprecating humor appearing in flourishes. The delivery is as blunt and direct as Morris’s extensive musical catalog, and Ruland does well here to not obscure Morris’s true voice in favor of more richly stylized prose. The result is a wild and no holds barred trip down memory lane to the beginnings of Southern California hardcore punk, and a look at the life and survival of one of its main progenitors. My Damage is not unlike other rock memoirs. Passages and anecdotes of spiraling excess (Morris smoking crack with David Lee Roth), battles with alcohol abuse, inter-band rivalries, and cautionary tales of the music industry are all here. What separates My Damage however, is the tenderness by which Morris describes his battles with addiction, diabetes, and a world that has been perpetually “up his ass.” Unlike so many of Morris’s peers, his tone is charmingly affable throughout My Damage, which gives it an endearing quality that is lacking in the memoirs of Morris’s peers.

My Damage not only chronicles the personal struggles of Morris, but also charts the nascent hardcore punk movement that helped shape not only the underground and DIY ethos of the scene in Los Angeles, but worldwide. We are given intimate accounts of the seminal Black Flag and Circle Jerks, the untapped promise of Morris’s oft-forgotten Bug Lamp, as well as his late career revival via his current outfit, OFF! For fans of the hardcore punk movement, My Damage provides more than enough to satisfy. Recording sessions for classic records like Black Flag’s “Nervous Breakdown” EP, and the Circle Jerks’ debut Group Sex, are all told in wonderful detail.

Morris also reflects upon Black Flag’s infamous early performances, including the legendary Polliwog Park performance, which cemented Black Flag’s reputation as anti-establishment torch bearers and all-around threat to the safe and sterile Reagan suburbia. Morris also looks back on encounters with the police, with some confrontations resulting in extreme violence and abuse. There are stories of riotous gigs in Hollywood, and of police rushing into venues in riot gear. Through these anecdotes, My Damage proves itself to be a chronicle of a different time, a time that is perhaps hard to understand in 2016, where a punk rock “threat” sounds absurd and infantile. The music Morris made with Black Flag and the Circle Jerks, was a very real perceived threat to Reagan’s America, and was truly transgressive on a level that is hard to comprehend.

Lesser known facts about Morris abound here. His somewhat untold story as self-proclaimed “A&R boy” for Virgin Records in the late 90’s and early 2000’s is described in some detail. His struggles adapting to the office world of fax machines, copy machines, and conference calls are particularly comical. His short comments on being sent by Virgin to see a Vampire Weekend showcase in New York City and being so disappointed that he left mid-set because they sounded like “Paul Simon’s backing band when he discovered world beat,” provided some laughs.

Beyond all the band tensions, touring mishaps, stoned rampages, and weighing in on the dross of the music industry, Morris’s fights with diabetes and addiction really take center stage here. In his conversational candor, Morris recalls falling into a diabetic coma in Norway, just hours before he was set to perform with Norwegian punk legends Turbonegro. There’s also the time Morris passed out and crashed his car while driving to Amoeba Records, due to toxic levels of acid in his blood brought on by the diabetes. His battles to remain sober are inspiring, and are written here to the point where his struggles become universal and relatable.

Ultimately, My Damage has something for even the most fringe fan of punk. For those looking to get an insight into the early hardcore punk scene, there is more than enough. For those looking for a cynical take on the music industry, that’s here in spades. For someone looking for an unlikely source of inspiration when it comes to battling diabetes and kicking drugs and alcoholism, look no further. My Damage holds no punches, and where it outshines other memoirs is in its ability to present true human spirit in a way that isn’t overreaching or self-aggrandizing. With My Damage Morris cements his place as the ultimate punk rock every-man. And we love him for it.

My Damage: The Story of a Punk Rock Survivor is available through Da Capo Press.

Hardly War by Don Mee Choi

Hardly War by Don Mee Choi

John Travolta Considers His Odds by Emily Hunt

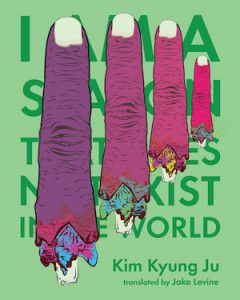

John Travolta Considers His Odds by Emily Hunt I Am A Season That Does Not Exist In The World By Kim Kyung Ju

I Am A Season That Does Not Exist In The World By Kim Kyung Ju