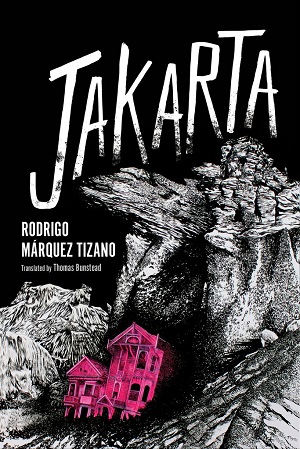

Written by Rodrigo Marquez Tizano

Translated by Thomas Bunstead

Review by John Venegas

What is the measure of a good piece of fiction? You’d think after all these reviews, I’d have a definition. But the truth is that no definition can ever be broad enough to encompass all the possibilities and specific enough to have any useful meaning. So it may be better to ask what makes this piece of fiction a good one. In this case, the fiction in question is Jakarta, by Rodrgio Marquez Tizano, and to be quite honest, I am writing this review to figure out the answer to that question. I’ve read it three times now and, after each reading, I’ve come away with two undeniable conclusions: 1) this a fucking fantastic piece of literature and 2) I can’t make sense of why. So here’s to hoping that putting words on digital paper might lend some clarity.

Though the city stagnates, and any possible works are safely buried under endless red tape, it’s still a place you never fully get a handle on.

On the most direct terms, this is a truly dystopian narrative. A first-person, non-linear dystopian narrative that teeters on the edge of magical (or perhaps sci-fi?) realism, all delivered by an unnamed protagonist. Right off the bat, the sense of dislocation and a lack of identity is intense. You are let loose in a world that goes largely unexplained and yet which is also disturbingly familiar, and your only guide is a person who won’t tell you their name and may not have the best grip on the flow of time, or their own sanity. It is, I have to say, a hell of a risky play. But damn does it pay off in the end. For one thing, I am always happy to see when an author trusts their audience to be smart enough to keep up. For another, the text is so well written that you find yourself following along almost through instinct alone, at least until you are so far in that you can’t really see the way back and you give in to the flow.

From Morgan’s notebook:

…

A story: the king asks the artist to paint him a labyrinth.

But it takes more than evocative sentence structure and clever wordplay to make a piece of fiction good, doesn’t it? What about the story? Dystopian fiction in particular always seems to be a misstep or two away from being a nihilistic masturbatory session for unprocessed immaturity. And yet here, Jakarta manages to be unrelentingly, mercilessly bleak, and yet somehow also funny and sweet and charming. The story allows you to empathize with people that, had someone just told you about their personalities, you’d probably never approach. It hands you existential questions with a sympathetic and regretful pat on the shoulder, not because it feels guilty, but because it knows you’ve been avoiding these questions for too long. I know this sounds pretty damn vague, but for however corny this might sound, Jakarta is a text to be experienced, not explained.

Maybe it is just me. Maybe this text comes along at the perfect (worst?) time for me. In the interest of disclosure, I am Latino, I am on medication to treat depression, I am a socialist, I am a former athlete and gambler, and I am living and writing this review while under stay at home orders to try and avoid the attentions of a global pandemic. When you read Jakarta, you will understand why all of that is relevant on the surface, but the reason I bring it up is that if we are going to consider that “good” may just be entirely subjective, then maybe this text is just letting me indulge that particular combination of young man’s angst and aging man’s bitterness, the parts of which I am just old enough to have a foot in.

Farther along the coast, beyond the ravines, the sky glows with a dirty light, like halogen lamps about to give up the ghost.

It takes a text like Jakarta, I think, to remind us of the purpose of literature, or perhaps the multi-faceted nature of that purpose. The purpose I speak of is empathy, the willingness and desire to recognize and experience (however second-handedly) perspectives that are not our own. Literature, like pretty much any art, is an act of understanding that we are not alone, that we want to be recognized and want to recognize in turn. And that recognition is not reserved for wholesome, or even bittersweet, experiences. If anything, we need solidarity and acknowledgment more than ever when we are isolated, when we are being oppressed and abused, when we are being fed narratives that are meant to distract us, deceive us, or render us powerless.

Addendum to idea: when I ask for my boulevard to have its very own median and for this median to be fitted in turn with a row of banana trees, Dos Bocas banana trees, the Secretary for Hydraulic Resources and Social Wellbeing gives me a tender look and exclaims: Don’t push your luck.

So have I stumbled upon an answer then? Is that what makes Jakarta a good piece of fiction? It’s probably as good an answer as I am capable of at the moment. The fact is that it is a wonderfully cathartic text, in the truest Aristotelian sense, one that tackles extremely difficult and unfortunately poignant subject matter and handles it with supremely gratifying deftness. To be clear, it is not a book that is going to appeal to everyone. But it’s also the kind of book that makes you realize what a damn shame that is.

Jakarta is available now through Coffee House Press.