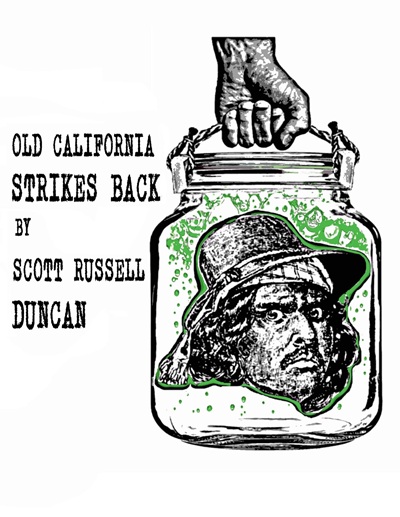

Written by Scott Russel Duncan

Review by John Venegas

Writing this review compels me, in ways others have not, to lay out my biases and bonafides. I can say here at the start that I will not be able to even pretend that I can be “objective” about Scott Russell Duncan’s Old California Strikes Back. This is a book about being multiracial, about being Californian, about being Chicano, and about all the baggage that combination brings with it. I am all three of those things, and my back has grown broad holding the bags, and I have no desire to pretend otherwise. With this combination of text and reader, there were only two ways this could have gone, from my perspective: 1) a flaming disaster that fails to launch and paints my people with the ashes of blood-soaked tropes, or 2) a brilliant act of defiance that encapsulates the bleakly hilarious absurdity of trying to enforce rigid definitions and celebrates the inherent, magnificent complexity of a people born of sun and soil. Friends, I cannot tell you how happy I am to tell you that Old California Strikes Back is most certainly the latter.

It’s not always clear what tradition requires of us, especially in sunny California.

There is a line in the Acknowledgements in which Duncan expresses dread at the idea of his family reading this deeply confessional text. He has good reason. This book is profoundly vulnerable and, as a result, lays out the little secrets we keep for all to see. Vulnerability is quite often punished in Chicano families, even loving ones, largely because vulnerability is so thoroughly and consistently exploited by White American society. Our families are messy. Our relationships are fraught. Our identities are shifting patchworks pieced together from the remnants of colonizers and colonized. And, in all of this, we are no different than anyone else. The text is a collection of journal entries, vignettes, testimonials, and memoirs that read like the frantically assembled notes of a half-mad archaeologist on the verge of enlightenment. They read like the scrapbook of a descendant worried they have started the project of preserving their heritage far too late but are compelled to continue anyway. There is a through-line, one might even call it a “Hero’s Journey”, but the narrative slowly coming into focus has no intention or need to resolve in predictable ways.

I wasn’t breaking too many laws, but the police kept their distance as they do when confronted with an army of animated revolutionary plants led by an angry Chicano cross-dresser. Joaquins stood impassive, swayed in the wind, and never raised their voice. We even welcomed guests. For a little while until they became bad guests.

It is strange, for me, to find such cathartic joy in a text that confronts denial and disappointment at its emotional core. The main character, an amalgamation of author and ancestor in constant flux, is constantly surrounded by both. His identity is denied from so many angles that it becomes far easier to label oneself as a contradiction. Disappointment is heaped upon him for being what he is, for not meeting a fetishized expectation set by the greedy and the ignorant. He is, at once, too much and not enough and therefore neither, othered to such an extent that his existence is exiled into indefinability. But there is, depending on your perspective, a silver lining. It becomes easier, from this vantage point, to become aware of the arbitrary ridiculousness of it all. There is a gallows humor to be had in watching some fumbling idiot get mad at you because they lack the breadth of imagination to begin to encompass who you are. And neither author nor main character shy away from their own failings, as vulnerability demands. There is a shame for the part one has played in these stereotypes, not in embodying them but in letting them color one’s own worldview. But that necessary admission of truth comes with an equally important acknowledgment that the lion’s share of the blame lies at the feet of the system that feeds upon us.

He, the tourist, is the actor, the poser. We, the Native, are the backdrop in his quest for the frozen and the ever-dying quaint.

You’re like the best of both worlds, I can tell my father you’re White and tell my mother you’re Mexican. Mexican guys are so hot….Call me a whore in Spanish.

Old California Strikes Back has a fascinating relationship to two fictional characters, the stories they came from, and the authors who created them. The first is Ramona, the heroine of the novel of the same name, created by Helen Hunt Jackson. The novel was written, allegedly, with the goal of bringing White attention to the brutal treatment of indigenous Americans in the wake of the Mexican American War. It, like most well-meaning fiction, had its message largely ignored by the intended audience, who instead focused on the stylized, romantic depictions of the colonial elite and aspired to be like them. The overarching narrative and many asides in Duncan’s book depict the hunt for Ramona, her famous jewels, and her descendants. To call this inspired by real events would be an understatement. Southern California still sees visits from tourists seeking to know if the book’s events were real. The other fictional character is Zorro. On the off chance you are not familiar with him, Zorro is a pulp hero created by Johnston McCulley. Zorro has many appearances across various forms of media – all the more considering that the character exists in the American public domain now – but his usual depiction is that of a vigilante swashbuckler fighting to defend the people of Alta California. The fictional Zorro does not really appear in Duncan’s book, but instead has his moniker pillaged and plundered and put to use with delusions of glory and entitlement. There are so, so many more references and allusions in Duncan’s rich text, but I am focusing on Ramona and Zorro because they embody the book’s defining struggle. They are White American idealizations of what it means to be Mexican, Chicano, indigenous, Brown, and more. They are heroes meant to inspire, and they do; just not always for the better.

I’ve written over it and pretended all the pages were blank, but when you write over text you can’t really read what’s new or see what’s underneath.

In the spirit of honesty, I must admit that there is more going on in this book than I can immediately identify with, but I find these elements no less compelling. I am not, for example, indigenous American, and I believe Duncan is (I find myself frustrated by the ineffectiveness of my language to encapsulate my meaning; to say Duncan “is” indigenous has a definitiveness that implies exclusivity, but you can be more than one thing. And yet, to question the certainty of “is” implies that you are questioning the entirety of the label rather than the label’s solitude. Here, I suppose, we find ourselves battering against the colonial mindset, a latticework, rusting cage of absolutes). This is one of those areas that I find some Chicanos struggle to come to terms with. Yes, we are the colonized, or at least the descendants of the colonized, but we are also the children of colonizers. Again, the text does not shy away from this idea. Failure to own up to all of our heritage puts at risk all efforts to lift ourselves and each other up, all efforts to find and build solidarity.

This caused me to believe Murrieta was Indian after all. Or an angry, confused Mestizo (as if there are any other kinds of half-breed).

This book is a fantastic read; funny without cheapening gravitas, grinning with defiance like the skulls on a tzompantli, irreverently reverent to the the dead, the living, and the yet to be in the hopes that all can come to know and build for one another. Like all good literature, it broadens your perspective, in this particular case so that you too might be able to give up trying to put people into boxes and demanding they stay there. I started this review by trying to be upfront about who I am, partially to excuse my unabashed praise, but also because this book helps remind me about who I am and that there is so much to love in where I come from.

Viva California. Viva la raza.

Old California Strikes Back is available now through FlowerSong Press.