Popular Musi c by Kelly Schirmann

c by Kelly Schirmann

The Crown Ain’t Worth Much by Hanif Willis-Abdurraqib

Review by Katharine Coldiron

In the middle of writing an ekphrastic novella based on an album I loved, I discovered to my surprise that music and literature don’t cross paths much. Bob Dylan is often viewed as a poet, and Yeats has been set to music by more than one artist, but still, it’s not often that the two media reflect on one another.

However, two small-press books of poetry from 2016 prove exceptions. Popular Musi

c, by Kelly Schirmann (Black Ocean), and The Crown Ain’t Worth Much, by Hanif Willis-Abdurraqib (Button Poetry/Exploding Pinecone) both explicitly call on musical influences to work at their subjects. In Schirmann’s case, the subject is life as a Millennial woman; for Willis-Abdurraqib, it’s life (and death) as a young black man. Both books explore multiple modes of poetry (often veering into prose), and both books boast artistic confidence and maturity well beyond debut-book status.

Schirmann’s poetry sticks largely to narrative and vignettes, but she causes small details to loom large. Most of her poems are no longer than a page, and some are even shorter. The narrative flow gives the reader the sense of sliding in and out of different parts of Schirmann’s mind.

All my friends

are moving to Los Angeles

She’s a fascist, says the Goodwill clerk

& hands me a new book

Wanting to learn a thing or two

is a dangerous position to be in

Girls just wanna have fun

says the loudspeaker

& the people swing

their brightly colored arms

As interesting as her poetry is, the prose is possibly even more effective. Popular Music is divided into six sections, alternating between prose and poetry. The prose segments each tell a single story almost as a fable, beginning with a memory and ending with a life lesson. That sounds tedious, but in practice it’s stunning. The prose also hits as hard as the poetry, if not harder, because Schirmann brings a poet’s sensibility to both rendering detail and making thematic connections.

Schirmann varies between real-life details and this kind of spare, unadorned analysis. She really shines, though, as her prose lifts into the lyric register toward the end of each prose section. “Music makes space for us, entire continents of space,” she proposes. “It provides us with new languages and images with which to describe it to one another, new emotional esthetics with which to interpret the experience of Living. It even provides us with a person to which we can outsource the interpretation of this experience. Out of this mouth, our feelings flow.”

This is definitely a point of view to which Willis-Abdurraqib would subscribe. His book is not explicitly about music, but musical artists of all kinds are name-dropped throughout it: Jay-Z, Taking Back Sunday, Nick Drake, Kanye, many more. One poem is named “At the House Party Where We Found Out Whitney Houston was Dead”:

We, the war generation.

The only way we know how to bury our dead

is with blood, or sweat, or sex

or anything pouring from wet skin

to signify we were here, and the wooden floor

of a basement belonging to an old house on Neil Avenue

makes as good a burial ground as any

says the small boom box now playing DJ

in the center of this room,

and the Whitney CD inside,

pouring out of the speakers just loudly enough

to let everyone in this room

get a small taste of Whitney alive and young,

Music is not the only thread that ties these poems together. The poetry takes multiple forms: narrative, visual, prose, couplets, and even sideways, the words running vertically from the bottom of the page to the top. However, the book is all of a piece. Partially this unity derives from a series of refrains: dispatches from a barbershop, memories of a shooting, a dead mother’s voice. The book also holds together via its recurring themes: violence, funerals, the urban environment, poetry itself, and, most importantly, blackness.

…And child, when you take skin swollen and damp from the river and the blood, and you throw it in the heat, everything pops. You gotta cover your eyes, baby. Hold them children close. My mama’s mama said that’s how God made the south. Said there was nothing but grass and then, one day, all this wet black skin. Said it popped so loud when they set them down in the blazing stomach of the new world, them plantation fields split clean open and then there was cotton. And then idle hands for the picking, and then war, and after that, we all woke up with our skin covered in hot grease, birds following us everywhere and so at least we was eating good.

Need I say more? Willis-Abdurraqib’s words speak for themselves more powerfully than anything I could say to recommend them. Read this book; live inside this poet’s skin. His is a poetic voice as strong and impactful as Ta-Nehisi Coates’s, a mourning, shouting, singing vox populi.

Popular Music is available through Black Ocean Press.

The Crown Ain’t Worth Much is available through Button Poetry.

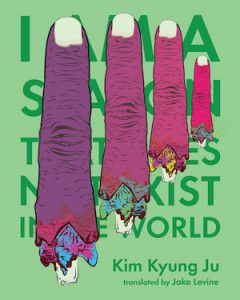

I Am A Season That Does Not Exist In The World By Kim Kyung Ju

I Am A Season That Does Not Exist In The World By Kim Kyung Ju