The Hermit by Lucy Ives

The Hermit by Lucy Ives

Solitude. The first thought that this concept strikes within me is one of solemn and despondent feelings. Of hopelessness, the sheer and unbearable weight of being alone in the world, existing in a place, real or metaphorical, where you are left to your own devices. However, within this place that real introspection can occur. Where one can begin to process life’s eventualities, the brief moments that make up the whole, and the successes and failures that makes life worthwhile. It is exactly these things that Lucy Ives is exploring in her recent poetry book “The Hermit”.

At first glance this book is quite sparse. Blank space is at a premium in this text with many sections encompassing only a paragraph, sentence, phrase or other musing. This is not to the books detriment though. The emptiness of it all forces one to be more tuned in to the feeling of isolation, but more so to the language that is being used here. Language that captures quite powerfully the feelings or ideas Ives had set out to explore. Words are examined with precision, ideas are tackled with ease, and the reader is forced to examine language in modes that may twist your mind theoretically. Ives use of language is at times quite lyrical, thoughtful, poetic, introspective, philosophical or all of these at once. Small moments in life, moments that may otherwise go unnoticed are given the chance to shine in the limelight of existence.

The book is hard to pin down because it is ultimately so many things at once. It is a book about process: the process of writing, writing poetry and prose, how art comes into that process, and all the things it can encompasses. But it is also a book about emotions, either miniscule in their initial impact or devastating in those moments of inception, that dig into you so deeply that they become a part of who you are. The idea of these moments and emotions cycle back and we are presented with how Ives takes these emotions and turns them into something beautiful. So we now cycle back to the idea of process, but not as course one takes in order to create, but as a means to make sense of the world, to heal, to cope with the weight of it all.

It is within this realm of process, that the book that Lucy Ives has written becomes something remarkable, personal, and quite human. Ives breaks down fragments of her existence into the pages of this book and lays them out bare. The reader is given a glimpse into a world that otherwise is sealed; and by the end of the book you may not understand a single thing, or you may now be privy to many things, however this exploration will no doubt open doors inside your own soul to allow the band of thoughts and memories, and emotions to play their song and hopefully make you dance, at least a little.

“What if a person will always be a few steps from life, whetever that is, and what if this person will feel dissatisfied, imperfect on account of this distance? What will we say to them? Do they become a character typical of their time? And, if such a person cannot become such a character, what is the use of them?”

The Hermit is available now through The Song Cave

John Travolta Considers His Odds by Emily Hunt

John Travolta Considers His Odds by Emily Hunt

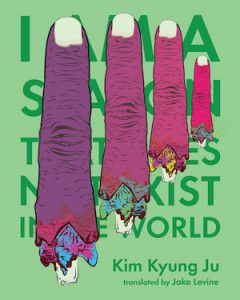

I Am A Season That Does Not Exist In The World By Kim Kyung Ju

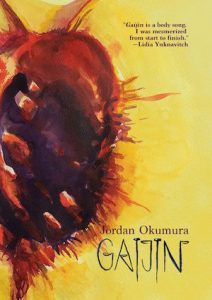

I Am A Season That Does Not Exist In The World By Kim Kyung Ju Gaijin, by Jordan Okumura

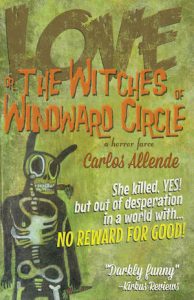

Gaijin, by Jordan Okumura Love, or The Witches of Windward Circle by Carlos Allende

Love, or The Witches of Windward Circle by Carlos Allende