After the Winter by Guadalupe Nettel

After the Winter by Guadalupe Nettel

Review by John Venegas

I don’t know that anything can be said to be simple anymore. Everything has its context and, in that context, everything attaches to a functionally infinitely complex weave. That’s not to say that people don’t desire simplicity – our brains seem hardwired to default to it – or that being comparatively simpler to something else is a good or bad thing. It just is. Given how aware we have become of the interconnectedness of our lives, I don’t know that it is possible to tell a simple love story and do justice to the complexity of people’s lives. So many of us seem to latch onto concepts like “soulmates” and “the love of my life”. We wait for the moment where “fate intervenes” and presents us with our “perfect match”, as if the cosmos owes us each individually one big favor for making us put up with its unfathomable enormity and sense of humor. Believe what you want to about the order of things, by all means, but I think we need the ironic reality check of books like Guadalupe Nettel’s After the Winter from time to time. It is a love story, an all too real love story, not because of how it ends, but because of how its characters truly live.

After the Winter is the story of Cecilia, a Mexican woman who moves to Paris to study, and Claudio, a Cuban man who lives an extremely orderly life in New York. From the start, it is clear that Nettel knows what kind of beast the romance genre has become. Pick up any such book from supermarket or airport shelves and you are almost guaranteed gorgeous cis men with “flaws” that only make them more attractive to heroines that are not aware of how beautiful they are and who have their value repeatedly ignored or denied. I do not disparage such works in the least – they possess an inherent and powerful value – but they do love their tropes, and from the opening page, Nettel is determined to show that After the Winter is not that kind of story. The text begins with Claudio, who proves himself to be uptight, aloof, arrogant, rampantly sexist, and dismissively judgmental. And that all comes across in the first chapter. The second chapter introduces us to Cecilia, a bookish, intelligent, reserved woman who doesn’t know how attractive she is but who possesses a determination that most do not expect from her. I’m sure that sounds like we are beginning to veer back towards trope territory, but Nettel knows exactly what she is doing, dear reader.

At different periods in my life, graves have protected me.

The rest of the book (mostly) alternates between Claudio’s story and Cecilia’s story as they wind and wind and inch ever closer to one another. We see their relationships, both platonic and romantic, and the nuances in how they see themselves and the world, as well as how they present to that world. We see their worlds collide, an event not entirely unexpected but one which plays out in a way that I definitely did not see coming and yet which, in hindsight, felt inevitable and natural. Most of all, we see how these characters, so very different from one another despite some mutual interests, deal with moments of bare vulnerability, of life being capricious and unfair in multiple ways. Love in these two almost parallel stories, including when they intersect, not as this supernatural force for good, or even evil, but as a naturally occurring connection between people that we can choose to embrace or ignore, and in what manner we do either.

My apartment is on 87th Street on the Upper West Side in New York City. It is a stone corridor very like a prison cell. I have no plants. All living things inspire in me an inexplicable horror, just as some people feel when they come across a nest of spiders.

It is at this point that I began to realize something, at least where my interaction to the book is concerned. After the Winter is not about love and its vagaries; it is a book about love’s relationship to death. I’m guessing at this point that I may be leaving you with the impression that this book is what many of us like to refer dismissively as “emo”. Don’t worry. In its determination to stare unflinchingly at its subject matter, After the Winter treats the heady intersection of topics with a mature honesty that is surprisingly rare in literature. Cecilia and Tom are not “star-crossed” lovers whom fate conspires against. Cecilia and Claudio were never fated to find each other. Rather, Cecilia is a beautiful depiction of reality, loving intensely, occasionally even to the point of danger. And Death becomes something akin to an unseen character in the final third of the text, whose presence looms and who stubbornly refuses to (or perhaps cannot) resolve our stories how we might wish. The point then, for telling this particular love story, seems to say that love is our statement, our testimony against death. It is our coping mechanism, our gift to ourselves and each other to remind us that we are not alone on our journey.

I want total silence to see if it is true that you have something to say to me, if you feel you did not interrupt the dialogue between us abruptly or if, on the contrary, you have disappeared for ever.

While all of this is compelling on its own, it is still possible for these emotional themes and character studies to fall flat on their faces if the writing isn’t doing them justice, and Nettel handles all of it beautifully. Her style is wonderfully efficient without losing a hint of intelligence, and the effect of this is a book that, while by no means small, is paced so well that you can devour it in a single evening if you are not mindful of the time. Some of the credit for this in the English version (which is what I read) surely has to go to translator Rosalind Harvey. The best translations are almost always the ones where you completely forget you are reading a translation at all, and I could not find a single mistake, awkward sentence, or moment that linguistically disengaged me. I find these things all the more impressive considering the whole of the book is delivered in first person (something many editors try to scare their authors away from) and that Nettel and Harvey never once fail in keeping the characterizations and narrative voices consistent and believably flexible. Both Claudio and Cecilia have distinct and strong personalities and make decisions you will not predict. Not all fiction has to feel so richly real, but the effect is undeniable and intense.

If there is any real criticism to be made, I will say that the quick pacing does not let up at the end of the novel, which makes the resolution to both stories feel very fast. But even there I cannot really fault Nettel or the text, because I can see that this might be intentional and, if so, consistent with the book’s themes about story resolution. In any case, I still whole-heartedly recommend After the Winter. It is the kind of book I want to show to people who still think that stories about people just living their lives cannot be dramatic and utterly compelling. It is powerful and fun and, at times, devastating in the most meaningful ways.

After the Winter is available now through Coffee House Press.

Inquisition, by Kazim Ali

Inquisition, by Kazim Ali Testimony of Circumstances, by Rodrigo Lira

Testimony of Circumstances, by Rodrigo Lira Othered, by Randi Romo

Othered, by Randi Romo Lessons in Camouflage, by Martin Ott

Lessons in Camouflage, by Martin Ott Drift, by Chris Campanioni

Drift, by Chris Campanioni Litane, by Alejandro Tarrab

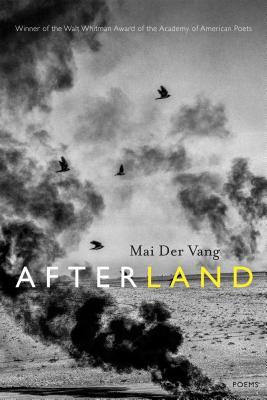

Litane, by Alejandro Tarrab Afterland, by Mai Der Vang

Afterland, by Mai Der Vang When People Die by Thomas Moore

When People Die by Thomas Moore Orange Lady, by Erika Ayón

Orange Lady, by Erika Ayón Calling a Wolf a Wolf

Calling a Wolf a Wolf Cadavers, by Néstor Perlongher

Cadavers, by Néstor Perlongher