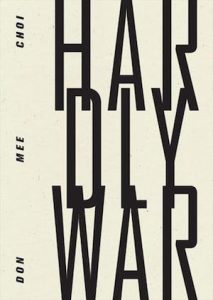

Hardly War by Don Mee Choi

Hardly War by Don Mee Choi

Hardly War is Korean-American poet Don Mee Choi’s latest offering and is a work that is boundless in its formal scope and the traumatic history it details.

The collection chronicles the Korean War through poetry, short prose, photographs, bits of letters, a postcard – and remarkably – an opera. Hardly War is a text that is in perpetual conversation with other texts, other histories, other forms. Choi alludes to and cites Korean avant-garde poet Yi Sang, children’s songs, films, Gertrude Stein, and French literary theorists. The dizzying degree of self-aware and referential academia within the collection might prove troublesome for some readers, but combined with the hybridity of the forms, and the accretion of allusions, quotes, and snippets, Hardly War becomes something more elevated than your typical literary experience. Hardly War is a brilliantly prismatic work, that proves itself to be a challenging but ultimately rewarding book.

At times Hardly War feels vaguely intrusive and deeply voyeuristic. Almost like Choi is giving the reader access to her family’s deepest and most wounded personal artifacts. The accumulation of the various hybrid forms and pieces of postcards and photographs – some with little to no translation or caption – amount to something like a vicious and mad index of the Korean war. The result is a deeply intimate look at the geopolitical climate and national identity of a Korea in turmoil during the 40’s and 50’s.

The photographs that scatter across Hardly War were taken by Choi’s father on his various trips as a war photographer throughout Southeast Asia during the Vietnam and Korean wars. Many of the photographs used in the collection don’t depict the violence of war, leaving one to wonder how much violence Choi’s father saw – or rather – was able to capture. Many of the photographs depict the faces of children or high ranking military officials. There are relatively little images of death – apart from some men posing with a tranquilized tiger – and nothing of explosions or gunfire. The closest we get to a semblance of war is a photograph of two expressionless children gazing into the camera, standing in front of a tank. The photograph is neither disturbing nor graphic, and the children don’t appear to be in any immediate danger. We aren’t even sure which side of the war they represent. An uncharacteristic war image to be sure, but as Choi reiterates throughout this collection, this was “hardly war.”

In a prose vignette titled “6.25,” Choi’s father hears the engine of a Yak-9 North Korean fighter jet, and chases after it with his camera in tow. The plane ultimately eludes him and he is unable to capture it on film. This is suggestive and symbolic of her father’s experience as a war photographer and works to illustrate one of the main overarching themes that we take away from Choi’s latest collection. Photographing the actual mechanics and physicality of war in any form seems to be elusive, and all we are left with is a smorgasbord of war time personal effects (i.e. photographs of children, postcards of military ships, etc). Hardly War in this way ultimately challenges our preconceptions of what war is supposed to look like and manifest as. The title itself, Hardly War, defines itself around the irony of what the war experience is supposed to be. For Choi’s father, and many Koreans, the war was “hardly” a war at all: “That late afternoon the yet-to-be nation’s newspapers were in print, but no photos of the war appeared in any of them. After all it was hardly war…”

Their is a heightened degree of playful self-awareness that marks Hardly War from start to finish. This is apparent in the various forms that make up the collection and in Choi’s stylistic choices. One vignette features several lines of Korean script followed by the line “I refuse to translate” repeated five times. This is one of the more rebellious gestures within the text that suggests feelings of resentment and anger towards the imperialistic and colonial nature of translation. The act of translation to English being a kind of western affront; a colonial gesture. However, given that the majority of Hardly War is written in English, Choi is perhaps suggesting that language is rendered moot and unreliable in its attempts to communicate anything in the face of war.

In the short piece titled, “Neocolony’s Colony,” we are given Vietnamese and English translation side by side. Each English line however, ends with an emphatic militarized “Sir!”

Me Binh Tai / Me been there, Sir!

Me Binh Hoa / Me been high, Sir!

The oppressive and imperialistic nature of translation is laid bare in this instance. Here, translation from Vietnamese to English is seen as an act of ultimate obedience, from a Vietnamese soldier to an unnamed high-ranking American military official – we presume. The result of reading the translation from Vietnamese to English across the page creates a dehumanizing effect, and as the piece moves down the page, the lines become more self-deprecating.

Me Phong Nhi & Phong Nhat / Me flunky & fuck that, Sir!

Me Tay Vinh / Me terrible, Sir!

The end of the piece is highlighted by ME ~ OW written in bold and all caps. Choi’s playfulness here touches a sentimental note, as we are given an allusion to the noise a cat makes, but also phonetically the phrase aligns with the crude and vaguely racist English translation of the speaker:

Me flunky…

Me hate milk…

Me terrible…

Hardly War is a brilliant and layered collection that forces us to reexamine the codes of language and our conceptual notions of war. An act of protest in itself, Hardly War gives us a fresh and often complex perspective on a war that is often called the “forgotten war.”

Hardly War by Don Mee Choi is available now from Wave Books.

Here Lies Memory, by Doug Rice

Here Lies Memory, by Doug Rice