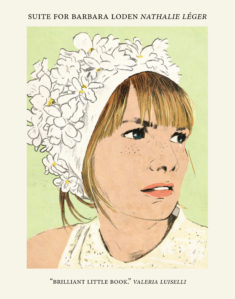

Suite for Barbara Loden, by Nathalie Lèger

Suite for Barbara Loden, by Nathalie Lèger

Translated by Natasha Lehrer and Cècile Menon

A little backstory: In 1970, Barbara Loden wrote, produced, directed, and stared in a film called Wanda, which was semi-autobiographical, inspired by the true story of a woman who thanked a judge for sending her to prison, and the only feature film that Loden would ever write or direct. Despite winning some early awards and critical acclaim, it was never widely distributed or seen in the United States. As of today, thanks to the efforts of a few dedicated and appreciative individuals, the film has seen a restoration and is gaining some of the notoriety it deserves. Enter Nathalie Lèger and Suite for Barbara Loden, a short novel that hybridizes literary styles in order to tell the not so simple stories of Barbara Loden, of Wanda, and of Nathalie herself as she attempts to construct the text from within and without. The result is nothing short of wonderful. As readers we are presented with a book that can exist in multiple spaces, resonating with frequencies that are simultaneously attuned for feminists, writers, survivors, and their allies. It is a book from which humbling messages can be gleamed or which can satisfy on a purely linguistic, structural level.

The hardest thing is the words, how long it takes, he says, taking a sip of his drink, the concentration you need to work out what goes with what, how to put together a single sentence. I had no idea that shaping a sentence was so difficult, all the possible ways there are to do it, even the simplest sentence, as soon as it’s written down, all the hesitations, all the problems.

The moment that quote is describing is an encounter with New York Yankees legend Mickey Mantle, and it elegantly encapsulates much of what is going on in Suite for Barbara Loden. The idea applies equally well to speaking or to writing, really any use of language, once your mind has been exposed to the possibilities of discourse. Through its own structure it displays the very concept it is explaining. The commas are the hesitations. The “concentration you need to work out what goes with what” is immediately evident – despite the constant pausing and reluctance and reconsideration, the sentences are grammatically correct throughout. Moreover, the spirit of the quote, even though it is put in the mouth of Mantle, flows through Loden and Lèger as character and narrator of this text. The care and deliberate choices being made give shape to truly unique and emotionally ensnaring read. And this permeation, this blurring of boundaries between entities and experiences, eventually leads to an immersion that combines the pieces of the text in eye-opening ways.

To sum up. A woman is pretending to be another (this we find out later), playing something other than a straightforward role, playing not herself but a projection of herself onto another, played by her but based on another.

The layering of reader, author, narrator, characters, and characters created by characters in this book is beautifully reflective and reality-distorting, akin to looking into one of two opposing and parallel mirrors as they echo into infinity. This extends to the book’s relationship to its visual counterpart. Like the film, the book never insists upon itself or makes claims at profundity. The language used, while consistently harmonious and contemplative, is never superfluous or pedantic. Several parts are delivered in a manner all too familiar to anyone who has written and read screenplays, though the attention to evocative detail in these sections is indicative of both a skilled prose writer who cannot abandon her craft and of a talented screenwriter who has a singular vision to put to page. Despite switching characters and focalization, the text’s pacing and tone make its constituent parts feel unified, further reinforcing the storytelling continuum that exists at the book’s center.

I know from experience that to gain access to the dead you must enter this mausoleum that’s filled with papers and objects, a seal place, full to bursting yet completely empty, where there is barely room for you to stand upright.

Have you ever been in a room that contains people talking, and perhaps you are even part of the conversation, and the quietest person in that room says something that catches you totally off guard with both its conceptual power and its simultaneous humility? That is the closest non-literary experience I can associate with reading Suite for Barbara Loden. I never cease to marvel at or enjoy texts that, in a relatively short space (this book isn’t even 120 pages), manage to capture the essence of depthless experiences. The book, like the film and actress it shadows, is an intricate, multi-faceted metacommentary on feminism, misogyny, film, personal identity, and, in the book’s specific case, writing. It wears the bruises of abuse and dominance as evidence of a contradictory, self-serving system that trips over itself in the effort to perpetuate. It explores the empathy and the obsession required to write and to understand someone else’s story. I sincerely hope that this book is spared the confused ignominy that kept Wanda as a relative unknown for so long, because it deserves to be read. By simply existing as it does, it earns its voice.

Suite for Barbara Loden is available now through Dorothy, A Publishing Project.