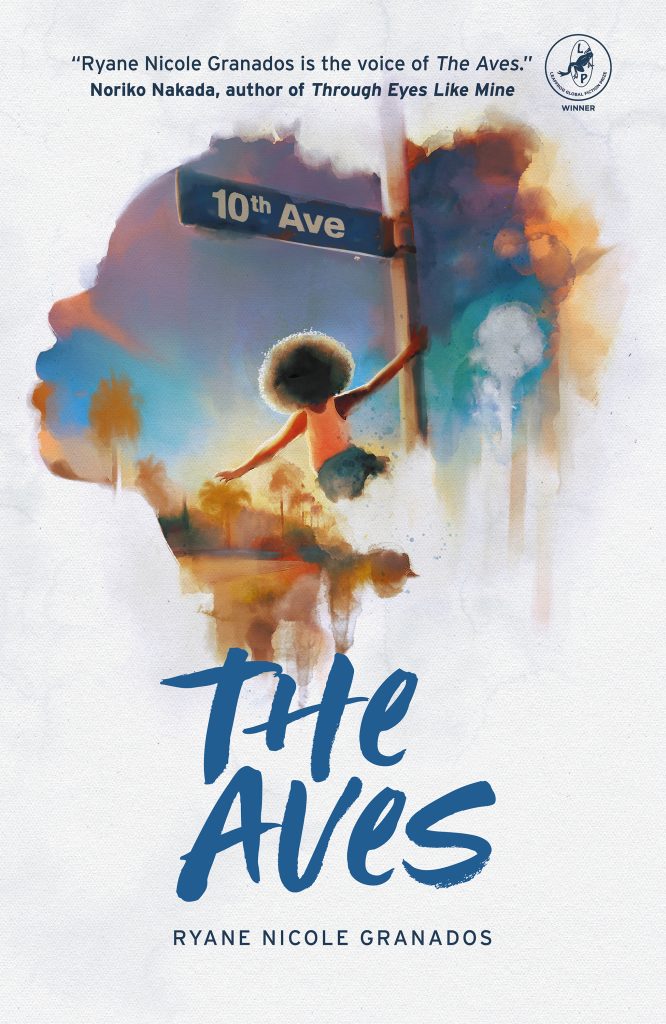

The Aves, Ryane Nicole Granados’ debut YA novella is a coming of age story of a Black girl in a South Central neighborhood in Los Angeles in the 70’s. The Aves pays tribute to Black women sisterhood while dropping wisdom in gorgeous language. What I most cherish from Granados’ delicate prose stands out in tight curls decorated with barrettes.

This opening passage sets the reminiscent tone and the pre-teen female voice that carries throughout.

“… I wore my hair in three pigtails. Mercy parted two in the back and left one on the top of my head, which she brushed to either the left or the right side. She snapped plastic barrettes on the end of each braid and coordinated the colors to match my outfit for the day.”

The main character Zora Neale Rebecca Hunter sits at a salon to have her hair straightened with hot iron rods, which brings memories of the coming of age ritual in the life of Black girls. The description of this event laced with the girl’s reactions and emotions take up the first four pages, indicating that having her hair done at a salon for the first time became part of her identity.

Hair plays an important role in this brief and powerful tale of sisterhood. Hair not only marks their entrance into womanhood. Additionally, it serves as an instrument to express the Black woman identity.

“Sauda’s only daughter, Imani, is two years older than me and she once claimed she was a direct descendant from royalty because she had true African blood in her. She said … my hair was too fine and slippery to come from pure Black ancestry. … It was settled we were both African Princesses. We pricked our fingers and mixed royal bloodlines to make our nobility official.”

In The Aves, Black women’ hair comes in all textures to display their femininity.

“If I owned her windstorm of hair, … I would run my hand from scalp to hair’s end and roll each strand around my index finger to get the attention of the cute older boys. . . I would never, no matter what my sisters did, or mother did, or brothers expected, of father demanded, wrap it away from the eyes of the world.”

Although there are some male characters in the story, they do not move the plot. They are the dark shadow on Imani’s life, or a fictionalized memory of Zora’s father, or a young husband, Tomi marrying the girl who grew out of the foster care, or Zora’s brother, James, who only has a few lines of dialogue instigating conflict between mother and sisters, or a homeless man writing a thank you note. The only male character with some significant participation is the neighborhood thief who acts as some sort of Black Santa Claus. He is funny and caricatured.

In contrast, women are the protagonists of the action, the ones that twist the plot, who make things happen. The readers never see the shadow of the man holding Imani captive, but we certainly see Mercy’s action that liberates the 15 year old from her dark life. We see Luisa, the girl fighting the boy in the middle of the neighborhood with all the toxic passion learned from her dysfunctional parents.

The reader can also see a working class, African American neighborhood in South Central LA, not far from the LAX airport, where airplanes are so close their noise interrupt an afternoon game. These are one or two parent households. At least one character has outgrown the foster care system. They have their dysfunctionalities that serve as neighborhood evening entertainment. They celebrate their joy and small accomplishments. Homelessness has already made its appearance in this 70’s setting, but even the most innocent and fragile character does not feel threatened by a poor man living on the streets. The thief plays Santa, but the single mother with high moral standards can’t accept those gifts. Granados has treated this neighborhood with the same love and sense of nostalgia that she treated her best female characters; thus, she reinforces the power of community in creating a strong African American identity.

Although Granados never deviates from showing us The Aves through the eyes of a pre-teen girl, it is through the master use of dialogue that the author drops adult wisdom.

“Regret is a wasted emotion, Zora. Envision a life that when you grow old you will one day want to remember, and then spend the time in between making that life come true.”

With its textured hair and bold female characters, Ryane Nicole Granados laces a sweet and brief story of sisterhood. The Aves touched my heart with a reminiscent tone bringing up the shared memories of rites of passage for Black girls. The young reader will be delighted to find a character that looks like her and feels like her. I am sure Middle Grade readers, especially Black girls, will cherish The Aves as much as their souvenir barrettes.

The Aves by Ryane Nicole Granados is available now through Leapfrog Press

Lisbeth Coiman is a bilingual author and an avid reader. Her debut book, I Asked the Blue Heron: A Memoir (2017) explores the intersection between immigration and mental health. Her poetry collection, Uprising / Alzamiento (Finishing Line Press, 2021) raises awareness of the humanitarian crisis in her homeland. Her book reviews have been published in the New York Journal of Books, in Citron Review and The Compulsive Reader, LibroMobile, and Cultural Daily to name a few. She lives in Los Angeles, where she works and hikes.