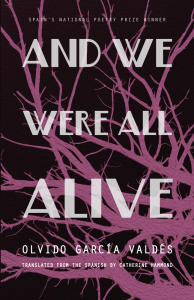

Collection by Olvido García Valdés

Collection by Olvido García Valdés

Translated by Catherine Hammond

Review by Benito del Pliego

Among the contemporary Spanish poets, few are better suited for a translation into English than Olvido García Valdés. Her poetry cannot be reduced to any of the stereotypes surrounding what any Spanish speaking poet —particularly female poets— should be like, and yet a fine-tuned reader will have the opportunity of noticing that she is not leaving behind key aspects of the conversation that, one may say, the Spanish poetry has been having in the last few decades.

What is it, then, that makes this translation such an interesting read in English? It is about what the poem pays attention to. It is about how the poet positions herself in the language of the poem.

And We Were All Alive covers just about half the original included in the book that received Spain’s National Poetry Prize in Spain in 2007. With few exceptions, the poems offered in the translation are short notes in verse in which an observation of the surroundings takes the reader to an unexpected place.

Between the literal meaning of what you see / and hear and another less obvious place, / inquietude opens its eye.

That inquietude, as many poems, seems to come from an unusual glance to common views, from a chain of reflections without obvious connections, from memories of dreams, from retained memories.

A few poetic strategies define the writing process here. Among them, the most prevalent are a variety of forms of juxtaposition, such as opposition, or transitions eased by some short of grammatical or lexical ambiguities that moves the poem from one place to another without apparent discontinuity. Sometimes the bridge is established by a discrete echo such as in:

…Explosions / or skin tight to cheekbone; / veins and rough texture, / deteriorating, unable to adapt, the denim jacket had the odor / of the person, the person and the odor…

In any case, since there is not juxtaposition without a previous cutting, the poems also have another striking formal feature related to what is elided. These are quite poems, contained poems.

Being mindful of these two qualities (juxtaposition and ellipsis) greatly facilitates the possibility of chasing the elusive sense that presides García Valdés writing. The capacity to displace what is literally said, while safeguarding the possibility of other meanings, opens up an area of mysterious truth, a truth impossible to state in any other way but the way it has been written. Here, perhaps, lays the key of the fascination caused by García Valdés poems.

One of the elliptical —and fundamental— elements of the poems is the nature of their subjects. The voice that articulates the poems is defined by her capacity to see and say, rather than by any presupposed category (cultural, national, political…). There is someone in the poem; it is a she, it is a she who sees and says. Her voice takes us to a kind of knowledge that has nothing to do with so called common sense. Like other aspects of the book, the subject is precise, but not limiting. The projection of the identity is not the goal of writing; it is just one of the dimensions of which the poem make us aware.

The poetic forms resonate and may define the topics that emerge from the poems: death as a looming possibility, the disconcerting nature of human relationships, the warming presence of nature – especially animals – and places… In what is said arises the possibility of an answer, even if it is only an evanescent one.

The translation of these pieces may look like a simple task considering what Catherine Hammond has achieved. Or simply reading García Valdés’ original. In both cases there is a deceiving sense of normalcy. The difficulty seems to be placed in the interpretation or the evaluation of the words we read, rather than in the words themselves. The subtle dramatic points where the poem shifts gears or makes a turn are, nonetheless, difficult to capture in a translation. Hammond gently wrestles with then in a way comparable to the approach favored in Spanish by the author; it is a matter of punctuation, or the resonance of a few words. In that delicate process, Catherine Hammond achieves the essential task without too many concessions to translators’ tendency to make the translation look more natural than the original.

The second element I think poses a very interesting challenge for the translator is the delicate balance between distance and affection that crosses the book. It’s not ease to parallel García Valdés’ austere – but elegant and warm – Castilian phrasing. It may be hard for many readers to respond to both languages alike, but I would like to encourage everyone to search for that subtlety. Luckily, Cardboard House Press facilitates that approach with a bilingual edition. And we were all alive carefully in both languages.

And We Were All Alive is available now through Cardboard House Press.

Benito del Pliego is a Spanish born poet, translator and professor at Appalachian State University, in North Carolina. DiazGrey Ed. has recently published, in a bilingual edition, one of his poetry books, Fábula/Fable. His poems have been included in anthologies such as Forrest Gander’s Panic Cure. Poetry from Spain for the 21st Century (2013) and Malditos latinos malditos sudacas. Poesía iberoamericana made in USA (México, 2010). He has translated into Spanish, in collaboration with Andrés Fisher, selections of poetry by Lew Welch, Philip Whalen, and Gertrude Stein.